Sexo Grammaticus Learns the True Meaning of Christmas

[The following essay was originally posted in December 2007]

The other night, by a beautiful coincidence during the first big snowstorm of the season, we turned down the lights and stretched out, wrapped up in blankets, to watch our favorite Christmas special, the Rankin/Bass claymation Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, which we have never missed once in all our lives. If you missed it yourself, you’ll be pleased to hear that Rudolph saved Christmas again this year, defying, forgiving, and ultimately annihilating the cruelty of those who’d believed it necessary to drive him away in order to preserve it. Along the way, we were again reminded that bumbles bounce, that gold nuggets are of little use to squirrels, and that female deer have long, sexy sexy eyelashes.

During the special, one of us commented on how surprised a lot of people would probably be if they knew how much we loved it. In fact, we realized, most people in this country would probably assume we hated it, and that we would be inclined to rip on people who watch it every year, even well into adulthood. Since exactly the opposite is true, this was interesting. And, like many interesting things, it was funny for a couple of minutes, and then horribly sad. So we decided to write an essay about it.

Now the reason, of course, that so many people would be surprised to learn that the 1585 Team makes a yearly ritual of the claymation Rudolph, is that Rudolph is a Christmas special, and we are atheists. Most of the country probably identifies us, and secular humanists generally, with the Abominable Snowmonster of the North, the Rudolph antagonist who “hates everything to do with Christmas.” Indeed, the right-wing media have gotten lots of mileage out of accusing us of waging a “War on Christmas.” Now, we should remind you that, as pertains to things like the “political incorrectness” of saying “Merry Christmas” instead of “Happy Holidays,” this is actually a matter of the various religions fighting amongst themselves—and since, as atheists, we regard all religions as equally crazy, it’s inaccurate to lay the entire controversy at the doorstep of atheism. Furthermore—and most importantly—we realize that Christmas doesn’t really have a whole lot to do with Christianity anyway.

Take Rudolph, for example. The story is about an anthropomorphic talking reindeer who triumphs over senseless discrimination and saves the day in the end. If liking this story requires belief in the divinity of Jesus, we certainly don’t see how, and we’re pretty smart. Sure, it contradicts the scientific position that reindeer can’t talk or fly, but it also contradicts the Biblical stance that animals are soulless and valuable only insofar as they are useful to humans. Aside from the historical accident of its having been thought up in conjunction with a Christian holiday, there’s no reason why the story of Rudolph “belongs” more to Christians than it does to anyone else—and no reason why the “anyone else” shouldn’t include atheists as much as Jews, Buddhists, Mandaeans, or anyone else who really likes the part where he goes “She said I’m cuuuuuuuuute!” and then is the very best at flying.

Now, on the face of it, there’s no reason for anyone not to like this, because clearly it is awesome. And we’re sure that there are Christians who use the fact that it is awesome as an argument for Christianity. But, as we’ve said before, Rudolph is only a Christian story on a technicality, and the same goes for Frosty, etc. None of these is a story from the Bible, and whenever someone tries to make a Christmas special that is a story from the Bible, it sucks ass. Claiming Rudolph for Christianity is like saying you have to convert to Judaism if you thought it was funny when Adam Sandler did “The Chanukah Song.”

The only even halfway-Christian thing about Rudolph is the fact that it involves Santa Claus—and, frankly, calling Santa Claus “even halfway-Christian” is pretty generous on our parts. On the pre-Christian year’s-end festival of Yule, the god Odin, in the form of an old man with a white beard, was believed by little pagan girls and boys to travel from house to house on a flying horse, slide down the chimney, and leave presents of candy (and the candy was shaped like letters, because the holiday ostensibly commemorated the invention of poetry—so as writers we are loathe to hand it over to you). Clearly, this was basically Christmas. Then the Christians got to that part of Europe, and what happened was more-or-less the following:

Christians: How about we start saying it’s St. Nicholas, instead of Odin?

Norse: Can we still give one another presents, and light pretty candles, and sing songs and eat candy?

Christians: Sure.

Norse: Then we could give a fuck. St. Nicholas it is.

We may have left a few things out, but anyway, that’s pretty much how we feel. People who live in places where it gets really cold and dark and shitty at this time of year have always wanted to have a big fun party right in the middle of it, because otherwise everyone would kill themselves (you will note that the importance of Christmas in Christianity increased alongside Christian incursion into places where the weather sucked during that season), and you have to call it something. The Danes and Anglo-Saxons called it Yule. We could try to bring that name back, but what’s the point? We don’t believe in Odin either.

Besides, they also called January “Wolfmonth,” so if we’re going to bring anything back, it should totally be that. People would be like “Hey, what month were you born in, because if it’s some pussy month we’re going to fuck with you,” and if you were born in January you could be like “fucking WOLFMONTH,” and then they’d be all like “Ahhh! Let’s get out of here!”

But this is irrelevant, because the Santa Claus of Rudolph—and of most Christmas specials and movies—is neither Odin nor St. Nicholas. He is a secular figure. He is ostensibly immortal and has magic powers, but there’s nothing in Rudolph (or in most Christmas specials) about his being appointed by the Christian God (or any god), or about him only bringing presents to Christian children. As far as we know, this Santa Claus answers to no-one, and brings presents to everyone.

And anyone who believes that this Santa Claus is an extension of the will of God is in big theological trouble, because the entire plot hinges on him being wrong about something. If Rudolph’s father had been the only one who had a problem with his glowing red nose, then Rudolph could just have toughed it out until he got his own place and everything would have been fine. But for some reason, Santa himself explicitly states that Rudolph’s nose will prevent him from ever being a part of the sleigh team—so the problem is not simply social teasing, but rather de jure employment discrimination. This is inarguably unjustifiable, and until his conversion in the last act, Santa comes off as not only flawed, but an asshole. And even at the end of the special, he’s far from perfect, because it apparently remains the case that only male reindeer can pull the sleigh (which, although he doesn’t appear in the special, means that Vixen is a boy—we can only assume that this led to Vixen eventually making a vow to kill the deer who give’m that awful name, finding him dealing stud in Gatlinburg in mid-July, and winding up kicking and a-gouging in the mud and the blood and the beer).

So, if you’re claiming Rudolph for Christianity on the basis that Santa Claus is an extension of the Christian God, then you also need to find a way to account for his shitty behavior. Or, at least, try to learn from how, at the end, he admits he was wrong.

Which brings us to the seemingly obvious matter of how that one elf is clearly beyond gay, which you guys have a problem with and we don’t. Sure, you can say that it wasn’t intentional and it just looks that way now, and some of you probably even try to say that we’ve ruined that special by trying to make people think that that elf is gay. But this is like saying that we’ve ruined nighttime by trying to make people think that it’s dark out at nighttime, because holy shit that elf is so gay.

You can say that all elves are fundamentally kind of gay to begin with, but this one is especially gay, even for an elf. You can point out that they’re just trying to make him seem different, and that people tend to process all difference as sexual difference—and this would be a good point, except for the fact that there were any number of ways they could have made him seem different besides making him talk with a lisp and designing him to look exactly like the girl elves. The other male elves don’t even have hair, and he has frosted tips sticking out from under his elf hat. He says he wants to be a dentist, but he might as well be saying that he wants to open the North Pole’s only Cher Museum. Actually, he might even be transgender rather than gay, since his name is Hermey (not “Herbie”—listen closely). You could say that this isn’t intentional either, and they just liked the name, except that it’s not even a real name.

Okay, we’ve made our point. But the reason we laid it on so thick there is because we are arguing that this was clearly intentional. It’s not like the special is from 500 years ago—it’s from 1964 (yes, Rudolph first aired in 1964, the year the ’60s started), and it’s not like all that stuff didn’t come off as gay then. In fact, Hermey’s appearance and mannerisms more closely approximate gay stereotypes from that time than they do gay stereotypes from now. The only difference is that, back then, the makers of the special had the advantage of knowing people would just assume this was an accident and not say anything (like the running “my master, Mister Bates” joke in Gulliver’s Travels, which was of course also intentional). We tried looking into whether any of the people at Rankin/Bass involved with Rudolph’s production were gay, but this was inconclusive (the only significant thing we found was that the special’s writer, Romeo Muller, apparently never married or had any kids—which could mean he was gay, or could mean he was just an exceptionally lucky straight person). In any case, Rudolph is explicitly an exhortation for tolerance of all stripes, regardless of whether anyone had gay rights specifically in mind (the line where the Misfit Doll sings “Wake up, don’t you know it’s time to come out?” is a coincidence… probably).

We’ve heard people argue that “dentist” was gay code from the early sixties—as in “Hey, what bar do all the dentists hang out in?”—but couldn’t find it substantiated anywhere, and have to admit it seems unlikely. Eventually, you would have just ended up getting your ass kicked by a bunch of real dentists—like when our friend’s little brother’s friend was working at KFC and selling smoke out of the drive-thru window and the code word was “extra biscuits” only eventually someone pulled up and said “extra biscuits” because they actually wanted extra biscuits and it turned out to be a cop.

True story. Anyway, that elf’s gay.

To return to our main argument, it is certainly not the case that atheists “have a problem with” any and all things to do with Christmas, or with any other religious observance. This is because, as just shown, “things to do with Christmas” can happen, or not happen, to overlap with values that we share with theists—the dynamic here is simplistically self-explanatory: in cases where your values overlap with ours, we share them, and in cases where they don’t, we don’t. The only Christmas-related belief inherent in atheism is that we don’t believe Jesus of Nazareth (or anyone else) was divine; we believe he was a mortal man. So, if that constitutes “having a problem with” Christmas, then we do, and if it doesn’t, then we don’t.

The fact that Jesus’s theological title of “Christ” is in the name for the day actually means little to most of us. The word for Thursday comes from “Thor’s day,” and we don’t believe in Thor either, so, logically, if we objected to calling Christmas Christmas, we would also have to object to calling Thursday Thursday, and we don’t. Neither, for that matter, do we want to pick a new name for element #80, commonly known as “mercury.” Many of us are annoyed by the expression “Jesus is the reason for the season,” but this is because we know that most of the elements constituting the Christmas celebration (e.g., presents to Children, decorated coniferous trees, and the date of December 25th) were amalgamated into Christian tradition from pagan observances that predated it—so our objection to that phrase stems from our desire for historical accuracy, rather than from a theological dispute. To get down to the heart of the matter, “Jesus is the reason for the season” is a false statement, whereas “flashing lights are pretty” and “it is fun to give and receive presents” are true statements.

But that’s not to say that we always distinguish between Christmas stuff that’s explicitly about Jesus and Christmas stuff that isn’t, because we don’t. We still like a lot of the Christmas music that is explicitly about Jesus, because a lot of it is simply good music. If we were going to reject all music that espoused Christian doctrine, we’d also have to reject Mozart’s Requiem, K.626 (among many other things), and we certainly won’t be doing that anytime soon, because awesome music is simply awesome music, regardless of whether you believe that the events described in the Bible literally happened. We don’t believe that the events described in Lord of the Rings literally happened either, but that doesn’t mean we don’t like Led Zeppelin, because Led Zeppelin fucking rocks. Is Christmas music often written and sung by people who do believe that the Bible really happened? Sure. But for all we know, the members of Led Zeppelin might believe that Lord of the Rings really happened. If they tried to take over the school board and get science curricula changed to account for the peculiar chemical properties of the One Ring, we would oppose them in this endeavor to the best of our abilities—but as of this writing, all they have done so far is fucking rock.

And this last paragraph is only half a joke—it’s as possible as anything else that, eventually, Lord of the Rings will become a religion. Tolkien was certainly a better writer than L. Ron Hubbard, and look how well Scientology’s done for itself. And the fans are certainly dedicated—if admission to midnight mass required Catholics to wait on line for three days, in costume, would they do it? And yet, if Lord of the Rings were to become a religion tomorrow, that wouldn’t mean that the people who didn’t believe in it that way couldn’t still like those books or those movies.

Likewise, Christianity will eventually stop being a religion. All religions eventually do. But when it does, we bet there will still be a big holiday of some kind around the end of December, involving lots of bright lights, and possibly a big pretty tree, and on which people sing fun songs, eat great food, and exchange gifts, and around which time women are hornier than at any other time of the year except possibly the beginning of summer. New traditions will have been incorporated into it too, and it may even morph into an observance of the life of other people in addition to, or besides, Jesus (we’re betting on John Lennon, since observances of his death fall on December 8th, which is two days closer to the 25th than is the feast of St. Nicholas, who got incorporated pretty seamlessly, and plus radio stations already play “Imagine” like it’s a Christmas song, despite the fact that the opening line is “imagine there’s no Heaven" ). And it’s entirely likely that this day will still be called Christmas, because there’s no particular reason to change the name—it’s just that the “christ” part of the word will have become a trivia question, just like the “thurs” part of “Thursday.”

In short, trying to get rid of all the words, names, and symbols that entered the language and culture via Christianity would be both impossible and unnecessary. It would mean, among other things, that we would have to refer to the bad guy from the old Mickey Mouse comics as something other than “Black Pete,” since this name is an Anglicization of the Dutch Zwarte Piet, Santa Claus’s assistant, a manifestation of St. Peter himself, whose face is dirty from climbing down chimneys. It would also mean that we would have to be against people hanging up cardboard vampire faces on Hallowe'en (vampires are repelled by crucifixes, and hence are a part of Christian mythology, right?).

Fundamentalists, of course, have been warning for years that the emphasis on Santa Claus, and presents, and fun parties dilutes what they consider to be the “true” meaning of Christmas. And you know what? They’re right. Those things are definitely in the process of eroding all sense of Christmas as an observation of the divinity of Jesus of Nazareth. But good luck stopping them. You cannot fight Frosty the Snowman and win. People like Frosty. He’s nice.

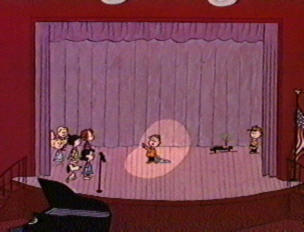

For the time being, however, we also like a lot of Christmas specials that do involve Jesus. A Charlie Brown Christmas gets explicitly Christian at the end, and we still love it. We think all little kids—and all adults, if they’re not too busy—should watch it every year, and Linus’s climactic recitation of Luke 2:8-14 does not change this for us. We consider it (as, most likely, do you) the highlight of the special, and more often than not it moves us to tears—the likelihood of this increasing, not decreasing, both with our aging further beyond childhood, and with the accompanying intensification of our “Culture War” with the people who believe in the literal truth of the words Linus recites.

Why is this? There are many reasons. For starters, we are smart, so we admire Linus’s impressive ability to memorize such a long and advanced passage of text at his age, and also identify with it, since many of us have fond memories of showing off in similar ways. Furthermore, in the context of the special, the recitation serves as the comeuppance of Lucy and her friends, who had just been ripping on Charlie Brown for coming back with an adorable real tree instead of a trendy aluminum one—and, regardless of one’s theological beliefs or lack thereof, Lucy is a universal antagonist. Finally, we are reflecting on how beautiful the nativity story is, and—but this is where we must part company with you—how wonderful it would be if it were true. But it isn’t.

Contrary to popular belief, atheists would be overjoyed if there were a God—we just don’t believe that there is one. It is inherent in human nature to wish that there were an omnipotent being who loved us at all times with a love beyond comprehension and guided us through our most exacting trials, and that death were an illusion, and that we would be reunited with our loved ones in Heaven, from which lofty vantage point we could kick back and watch Nazis and child-murderers burn in Hell. It is also inherent in human nature to wish that Hogwarts Academy were a real place, and that a fully-functioning lightsabre could be purchased in Wal-Mart for the rolled-back price of $29.95. But none of these things is true. You could ask us for the millionth time how we know that none of these things is true, and for the millionth time our answer might not satisfy you. But if Robert Plant asked us how we know the Battle of Evermore didn’t really happen, our answer might not satisfy him either.

Linus, of course—who we did admit was smart a little while ago—appears to believe in the words he recites. He also, as we know from the Hallowe’en special, believes just as fervently in the Great Pumpkin—or, at least, in sincerity, in which, at his age, he needs validation from a more powerful being to trust. All of this can be forgiven, because Linus is seven years old.

And Linus will be seven years old again next year, and the year after that. And we wouldn’t have it any other way. It must be mentioned, however, that if he were to grow up, he would be statistically the least likely of all the Peanuts still to believe in God, since he appears to have the highest IQ. And in this impossible future, after barely escaping high school with his life, graduating college with highest honors in Philosophy, scraping through a grad student’s existence on a few hundred dollars a month, and having his heart broken numerous times by deathly pale girls who wear cat’s-eye glasses and decorate their bedrooms with pictures of Rimbaud and Bettie Page and smoke unfiltered cigarettes in the shower—long after leaving the, actual, original “security blanket” behind—Linus might once again be asked what Christmas is all about. We think his answer might be something like the following.

Spotlight, please.

Winter happens because, for part of the Earth’s rotation, the Sun’s rays hit it less directly, making it colder on that part of the planet than it is during the rest of the year. The difference in temperature is a pittance in the grand scheme of things—a few dozen degrees—but makes an incredible difference to living things. Most plants die, and many animals hibernate or otherwise seclude themselves. The water on which all life depends freezes into ice, and the moisture that remains in the air falls not as rain, but as snow—a sea of innumerable tiny, fragile solids that together transform the landscape’s diverse individualities into a single continuity; its many colors, into one color. This is neither good nor bad, but simply the way things work in certain places on our little planet. The seedlings of the plants killed by the first frost are insulated by the snow’s cover, and nourished up through the soil by its melting. The fat, furry animals that live in these parts of the world exist in their present forms partly because of the winter, however little they may enjoy it. But human beings first became distinct from apes in the sun-soaked grasslands of West Africa, courtesy of an evolutionary process called neoteny—the retention of juvenile characteristics into adulthood. We lost the hair that we could never have afforded to lose elsewhere on the planet, but also extended the range of our capacity to learn, and greatly increased both our aptitude for teamwork and our need for community. Thus, when ancient humans first traveled into parts of the world where winter existed—driven by the hunt for resources, our natural curiosity, or perhaps the bitterness of some long, long forgotten feud—we were able to clothe ourselves, devise and build together shelters sufficient for the cold, and live in them together through those unforgiving months. And if bodily survival were all that humans required, our story would end here. But concerning all manifestations of hardship and terror—most centrally death itself, and winter is the death of the year—humans have done and will always do two things: seek to augment the sum of our knowledge with answers to the questions of why, and utilize the knowledge we already have, or think we have, to devise ways to make them as bearable as possible. Thus, the earliest civilizations invented explanations for the existence of winter—several such legends, from cultures that later ones presumed to call heathen or barbarian, tell of a beautiful Nature spirit married to the lord of the underworld and residing with him for a portion of the year, implying that humans have always desired our explanations, even for those things that most challenge and frighten us, to be rooted in the phenomenon of love as it came to be known to us. And it also came to be true that humans devised wonderful celebrations to be observed at such time as winter was at its darkest, noticing that the year’s shortest day marked also the time from which the days would continue one by one to lengthen, and so brought with it always the promise that the spring and the summer would return. We were able to look at the endless white that logically meant only death, and see a form of beauty as real as any other. The Scandinavian Yule celebrated the gift of language from the god Odin, who was said to visit houses in the form of a bearded old man and leave rune-shaped candy for the children. The Celtic peoples had Lá an Dreoilín, on which the children wore masks and ran from house to house accompanied by musicians, and Hogmanay, on which a visit from a friend was necessary to bring luck throughout the coming year. In parts of central Asia, Pongal was celebrated, with the daylong boiling of a sweet mixture of fruits, rice and milk; in other parts, Sankranthi, with the wearing of beautiful clothes. On Korochun, the Slavic peoples danced together in long chains, and burned fires in cemeteries to keep their ancestors warm. In China, Dōngzhi was a day on which to be with family; In Japan, comic plays were staged in public all through that longest night, on which it was said the goddess Amaterasu was tricked into seeing her own reflection in a mirror, and was so inspired by her own beauty that she returned to the world of the living. The children of the Germanic tribes left shoe-shaped cakes by the hearth to welcome Perchta, goddess of light, who would momentarily endow the wisest members of the family with the ability to predict the future. The Roman Saturnalia festival involved merrymaking so great that masters even traded places with their slaves; presents were given to children on the Juvenalia day, which also marked the rebirth of sol invictus, the undefeated sun—December 25th. When a certain sect of Jews accepted a teacher and philosopher named Jesus, who stressed love and forgiveness above all things, as their messiah, they began to call themselves Christians, and their beliefs eventually spread across Europe, and many Winter Solstice traditions were incorporated into an observation of his birth, the Christ’s Mass. When this observance spread to other continents, it likewise combined with the many diverse celebrations long practiced by the people in these places. Today, Christmas, or its equivalent in another language, is the term most commonly used in the cold, wintry parts of the world for the festivals that human beings have always used to brighten up what would otherwise be the most miserable time of the year. We know it isn’t really Jesus’s birthday, but very little about the day and its value has anything directly to do with Jesus anyway. In all places, throughout the history of civilization and well before, human beings who were completely isolated from one another had all independently decided to reinvent the darkest time of the year, when the face of death is closest to our own, as a celebration of all that makes life most worth living: warm fires, delicious food, fine clothes, family, joy on the faces of children, dreams for the future, great art, and love. Jesus is not the reason for the season. We are.

That’s what Christmas is all about.

Sexo Grammaticus is Lord High Editor of The 1585.

------------------------------------

Sexo Grammaticus is Lord High Editor of The 1585

- Printer-friendly version

- Login to post comments